Exhibition

The Mucha Museum - the only museum in the world dedicated to the life and work of the world-acclaimed Czech ART NOUVEAU artist Alphonse Mucha (1860 - 1939), was opened in Prague to the general public on 13 February 1998.

The museum is divided into seven sections exhibiting:

Decorative Panels; The Parisian Posters; Documents Décoratifs; The Czech Posters; Oil Paintings; Drawings and Pastels, Photographs and personal memorabilia of the artist.

The exhibition is completed by an interesting documentary on the life and work on Alphonse Mucha.

A number of items, previously part of the Mucha family home in Prague, are now on exhibit.

Section 1. Decorative Panels

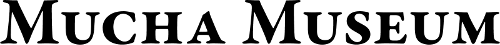

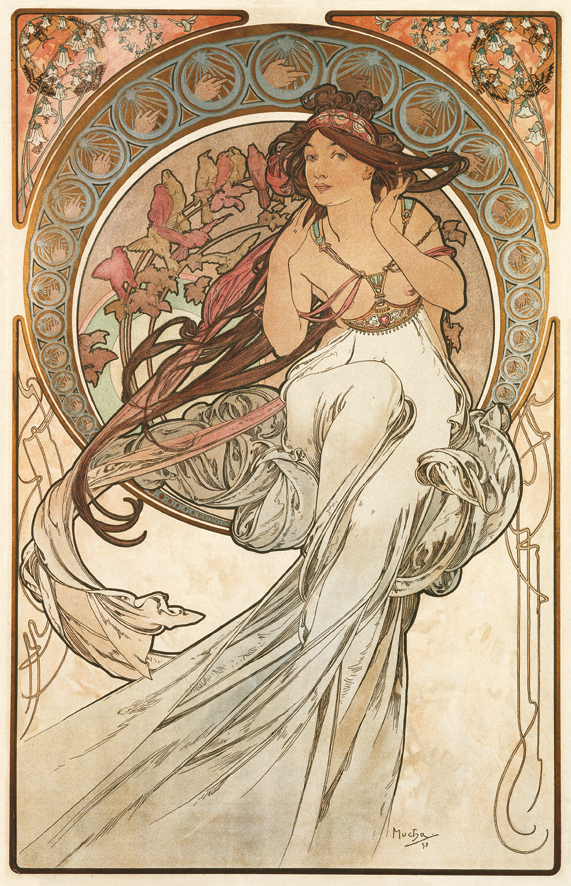

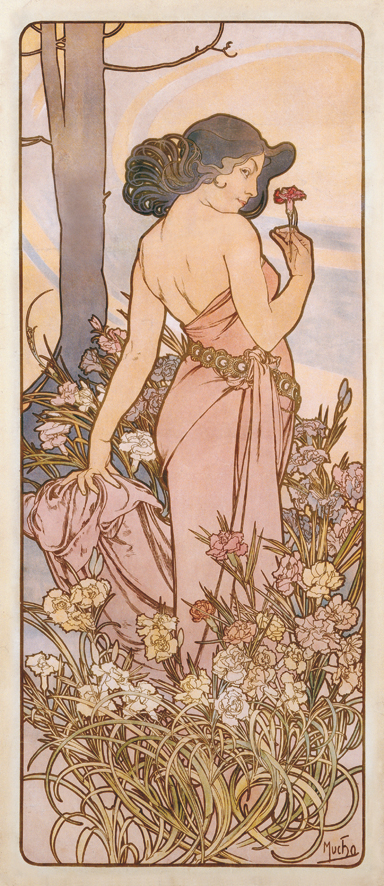

Alphonse Mucha was a leading exponent of the Art-Nouveau style, which demanded the creation of a decorative scheme that would allow for the repetition of stylistic patterns. Mucha based his work on an image that lent itself to an arrangement in cycles based on traditional themes, usually drawn from the physical world. For this reason, Mucha gave his first set of decorative panels, made in 1896, the title The Four Seasons. He continued this practice with a number of highly successful panels which respect the fourfold or twofold variation on a theme, including The Four Flowers (1898) and The Four Times of Day (1899), originating during the period when Mucha’s style was already fully developed. The stylized combination of vegetation and beautiful women was an expression of his joyful vision of life, one greatly appreciated by his audience at the time. From the artistic perspective, The Four Arts cycle (1898) can be considered the most serious among these cycles, executed in several techniques and distinguished especially by the poetic quality of Mucha’s designs.

The Four Arts cycle

In his cycle glorifying the four arts, Mucha deliberately refrained from traditional attributes, such as plumes, musical instruments and painter’s paraphernalia, instead setting each of the arts against a background related to a time of the day; morning for Dance, midday for Painting, evening for Poetry and night for Music.

Dance (1898), Painting (1898), Poetry (1898), Music (1898)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

The Four Times of the Day

Four female figures represent the times of the day, each set in a natural environment with an intricate framing, reminiscent of a Gothic window.

Morning Awakening (1899), Brightness of the Day (1899), Evening Contemplation (1899), Night's Rest (1899)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

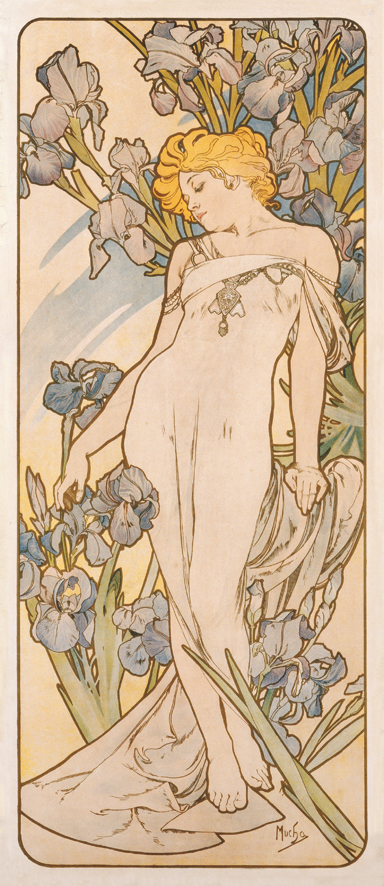

The Four Flowers cycle

For this cycle, Mucha selected a more naturalistic approach, demonstrating his sensitive and attentive observation skills in rendering the flowers’ characteristics. The original watercolours of two of the flowers, Carnation and Iris, were presented at the Mucha Exhibition in Salon de Cent in June 1897, however, the entire cycle was not available until the following year.

Carnation (1898), Lily (1898), Rose (1898), Iris (1898)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Section 2. Parisian Posters

Posters made in Paris in the 1890s form the best-known and world famous segment of Mucha’s work. It was through them that he managed to promote his own version of the new decorative style. The primary group consists of posters for Sarah Bernhardt, who was a famous Parisian actress. The first of these, created at the very turn of 1894 and 1895, portrayed Bernhardt starring in the role of Gismonda. Extant designs and print proofs for this poster demonstrate, through its stylistic and mainly colour conception, Mucha’s intensive search for a new poster image despite the short time he had for this commission. His artistic revolution brought a certain new elegance to the hitherto highly colourful “street salon”, thus increasing the newly found importance of the poster for modern art. The Bernhardt posters however also include dramatic tones (Médée, 1898). The scope of Mucha’s design activity was remarkable, ranging from subtle and stylistically refined posters for the artistic milieu (Salon des Cent, 1896, 1897) to the robust large-format designs for commercial purposes (JOB, 1898, Cassan Fils, 1896). All of them display Mucha’s extraordinary ingenuity and a sense of visually effective form.

Gismonda (1894-5)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Gismonda

This is the poster that made Mucha famous. The story of its creation is legendary, with many commentators arguing over its details. There is no question that Mucha himself saw the hand of fate in the circumstances which led to the creation of this poster.

The story took place at Christmas of 1894. Mucha was doing a favour for a friend, correcting proofs at Lemercier’s printing works when Sarah Bernhard called the printer with an urgent order for a new poster for Gismonda. All of the artists who normally worked for Lemercier were on holiday and so he turned to Mucha. A demand order from “the divine Sarah” could not be ignored. The poster that Mucha produced was revolutionary in its genre. The long, narrow shape, soft pastel colours and the stillness of the figure captured in a near-life size produced a surprising sense of dignity and gravity which was quite startling. The poster became so popular among the Parisian public that some collectors would bribe the bill stickers to get it, while others would even cut them out from the hoardings at night.

Sarah Bernhardt was delighted with the poster, immediately offering Mucha a six-year contract for the creation of stage and costume designs and posters. At the same time, the artist also signed an exclusive contract with the printer Champenois for commercial and decorative posters.

Gismonda, proof print

The two original proof prints for Gismonda are quite interesting. Mucha’s poster was too long for the common size of the printer’s stone and so it was assumed that it had been printed on two stones. Proof print however proves that it was printed using a single stone. The deep pink and yellow tones used in proof print indicate that Mucha originally conceived his poster in the bright hues fashionable among contemporary Parisian artists, such as Cheret and Toulouse-Lautrec, developing the softer pastel shadows, which were typical of Gismonda, while working on this poster.

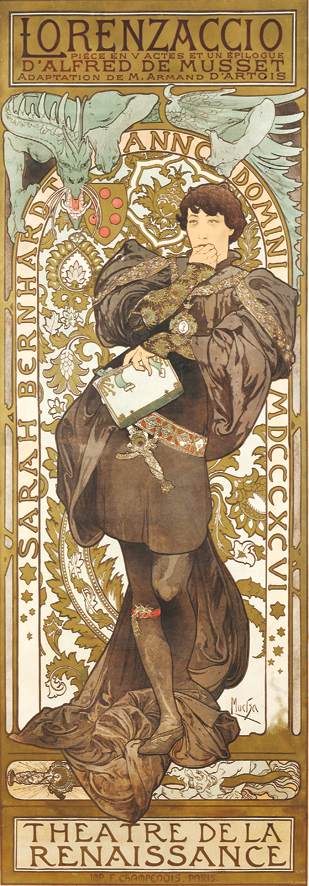

Lorenzaccio

In Alfred de Musset’s play Lorenzaccio, Sarah Bernhardt played the male hero, Lorenzo de’ Medici, at the time of the siege of Florence by the tyrant Duke Alexander, who is symbolically rendered as a dragon menacing the Florentine coat of arms. Lorenzo contemplates the murder of Alexander, which is depicted in the bottom segment of the poster.

Médée

Playwright Catulle Mendes adopted Euripides’ classical text especially for Sarah Bernhardt, depicting the Greek hero Jason, hitherto perceived as an untouchable mythological ideal, as a ruthless deceiver who had betrayed all who loved him in pursuit of his selfish passions, thereby giving Médée the psychological justification for her terrible crime. The poster renders the substance of the tragedy through a lonely figure. The mosaic background and letter “D” of the Greek alphabet situates the play in ancient Greece. Médée’s gaze, full of horror, is fixed on the shining dagger in her hand, stained with the blood of her children who are lying by her feet. The unusually detailed hands and the serpentine bracelet adorning Medea’s forearm are quite remarkable. This bracelet was designed by Mucha during his work on the poster and Sarah liked it so much that she commissioned jeweller George Fouquet to create a snake bracelet and a ring embellished with gemstones for her to wear on stage.

Hamlet

Sarah Bernhardt starred in the main male role in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, translated into French for her by Eugène Morand and Marcel Schwob. Behind the central figure of Hamlet, the ghost of his murdered father haunting the ramparts of Elsinore appears in the background. Ophelia, who had drowned, lies, decorated with flowers, in the segment by Hamlet’s feet. Hamlet was the last poster Mucha made for Sarah.

Lorenzaccio (1896), Médée (1898), Hamlet (1899)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Job (1898)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Job

Mucha made two promotional posters for JOB cigarette rolling papers, both featuring a woman with exceptionally abundant hair, holding a cigarette whose smoke whirls around her head. In this, the larger and later of the two, the woman is set against a circular background, which is in turn placed in front of a surface featuring the company’s initials.

Zodiac (1896)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Zodiac

One of Mucha’s most popular designs, Zodiac was originally made for Champenoise as an 1897 in-house calendar. However, the editor in chief of La Plume liked it so much he bought the rights to distribute it as the magazine’s calendar for the same year. There are at least 9 versions of Zodiac, including this one, which was printed without any accompanying text to serve as a decorative panel.

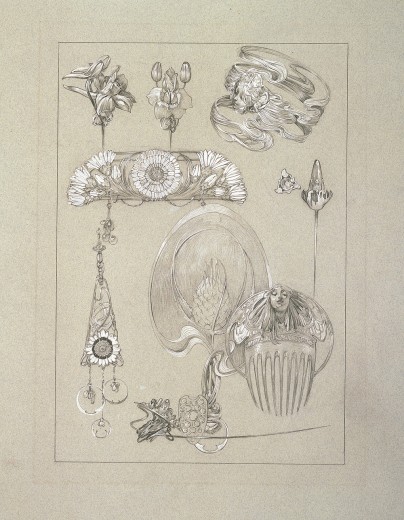

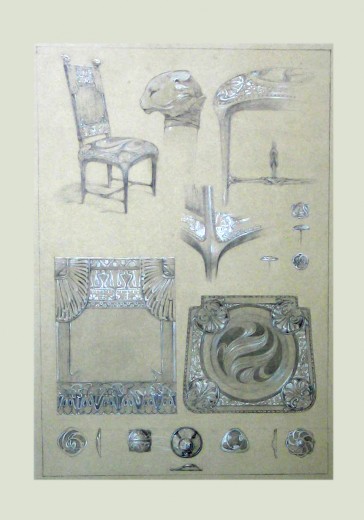

Section 3. Documents Décoratifs

In 1902, Mucha published a collection of 72 plates with patterns, drawn in pencil and brightened with white paint, for stylistic work in arts and crafts, titled Documents Décoratifs. This portfolio includes various ornamental and naturalistic floral motifs, studies of women’s heads, and nudes, combining illusive naturalism with abstract ornamental framing. Jewellery, furniture, tableware and many other items related to domestic life at the time suggest that Mucha strove for a summary of his extensive experience in decoration, which, especially considering his work for the Paris World’s Fair of 1900 and the interior design for the Fouquet Jewellery Shop, left a two-dimensional plane expanding into three-dimensional space. He aimed to create a comprehensive sampler for the new style. Although the Art-Nouveau epoch was coming to an end, one cannot help but admire Mucha’s draughtsmanship, demonstrated in Documents Décoratifs, as well as his stylistic ability to capture the entire world of objects in one spirit, as though permeated by the power of natural growth.

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Section 4. Czech Posters

After his permanent relocation back to his homeland in 1910, Alphonse Mucha returned to his long-held desire to systematically and single-mindedly, through his art, address his fellow people and express their needs and ideals. Gradually a new set of posters emerged, quite distinct in design from the Parisian ones. There were two prevalent themes: a new approach to folklore, emphasizing the colourful beauty of Moravian costumes and the gentle type of young Slav women (Moravian Teachers’ Choir, 1911), and the theme of the sports events and festivals of the Sokol organization, which had been a symbol of Czech national self-determination since the 19th century. In addition to these, there are also posters that strongly denounce the oppression of the Slavs (Lottery of the Union of Southwestern Moravia, 1912) and lyrical recollections of Parisian motifs (Princess Hyacinth, 1911). In these works, ornaments are subordinated to the melody of the line.

Princess Hyacinth (1911)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Princess Hyacinth

The poster for Princess Hyacinth promotes Ladislav Novák and Oskar Nedbal’s pantomime ballet, starring popular actress Andula Sedláčková. The hyacinth motif recurs throughout the design, from the embroidered garments and spectacular silver jewellery to the symbolic circle held by the princess.

Moravian Teacher's Choir (1911)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Moravian Teacher's Choir

The Moravian Teacher's Choir was a choral ensemble, whose repertoire ranged from classical to popular and folk music, including compositions by Leoš Janáček. The choir toured in the Czech Lands as well as throughout Europe and the United States. The poster features a young woman wearing a folk costume from the Kyjov region, depicted as an attentive listener. Her figure is reminiscent of the decorative panel of Music from The Four Arts cycle.

Lottery (1912)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Lottery

The tone of this poster reflects the anti-Germanisation spirit typical in the 19th century. The lottery was one of the methods used for raising funds for education in the Czech language. The poster features Čechia, a symbolic mother of the Czech nation, sitting in despair on a dead tree, her hand resting on a wooden statue of the three-faced pagan god Svantovit, the protector of the early Slavs. The schoolgirl, carrying books and pencils, gives the viewers a reproachful look, demanding support both for her education and for the ailing Čechia.

Section 5. Paintings

Alphonse Mucha is primarily known as a draughtsman and graphic artist, however, the training he received at the Academy of Art in Munich also included painting. In the 1890s, Mucha engaged primarily in commissions in the field of graphic art and his paintings include mostly portraits and uncommissioned portrait studies. At first, Mucha painted his larger allegorical paintings using tempera (Prophetess, 1896), turning to large-format oil painting only after the relaxing of stylistic constraints and the discovery of the great theme for the cycle of paintings from the prehistory and history of the Slavs, at the beginning of the 20th century. The enigmatic Woman in the Wilderness (also known as Star, 1923) demonstrates Mucha’s great skill in this genre, combining realism and symbolism to create something exceedingly more substantial and challenging than a mere continuation of the tradition of historical painting. The artist fully explored this potential in his cycle of paintings known as the Slav Epic.

Prophetess (1896)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Star

Mucha made at least four preparatory studies for this image of a Russian peasant woman whose calm pose demonstrates her acceptance of her inevitable fate. This painting, also known as Winter Night and Siberia, expresses Mucha’s deep feelings for Russia and its people. Mucha visited Russia in 1913 to paint preliminary sketches for one of the Slav Epic’s canvases – The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia: Work in Freedom is the Foundation of the State. His photographs from this trip feature a number of Russian peasant women, similar to the woman in Star, however, it was Mucha’s wife Marie who posed for this painting. Mucha may have made this painting in reaction to the terrible suffering endured by the Russian people after the Bolshevik Revolution. Between 1918–1921, the country was buffeted by a civil war, which resulted in economic crisis and famine that killed millions in the Volga regions.

Star (1923)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Section 6. Drawings and Pastels

The presented set of drawings attempts to, at least briefly, reveal the remarkable creative background Mucha’s work had in drawing. This applies not only to the precise pencil drawings made as studies, but mainly the sketches which frequently exhibited an unusually expressive facture (Design for a window, ca 1900).

Design for stained-glass window in the St Vitus' Cathedral in Prague

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Section 7. Studio and Photographs

In the second half of the 1890s, Mucha made a remarkable set of photographs of female models in his studio in Rue du Val-de-Grâce in Paris. They by far surpass the standard contemporary use of photography as a cheap medium for preliminary studies as they capture the unique atmosphere of the entire studio, an artistic world in its own right. It was in this studio that Mucha entertained countless Parisian writers, artists, musicians and where he screened the first films by the Lumière brothers. In the background behind the models, whose poses are often reminiscent of the figures in Mucha’s Art-Nouveau posters, the artist’s own works can be found as well as various bizarre and oriental items and textiles, piles of books, and furniture, whose individual pieces have been preserved to today. They can be viewed in this exhibition arranged into a small studio setting. Exhibited photographs are reproductions from the original glass plates.

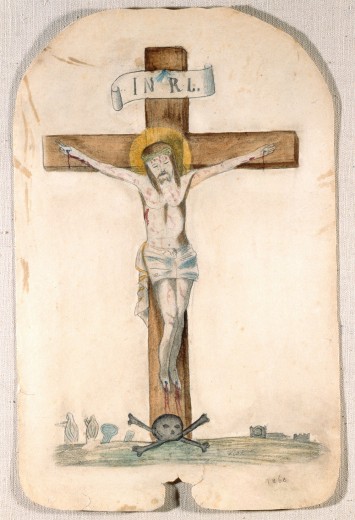

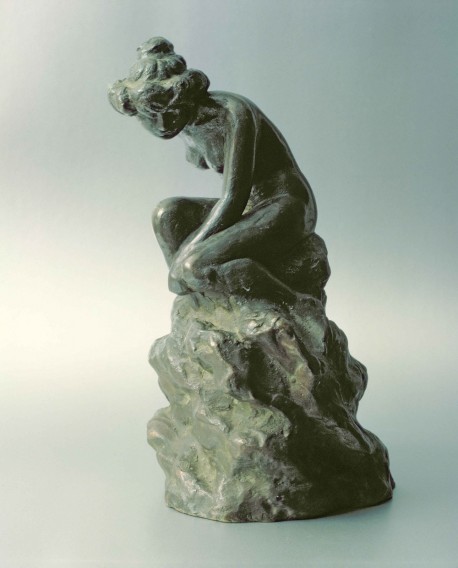

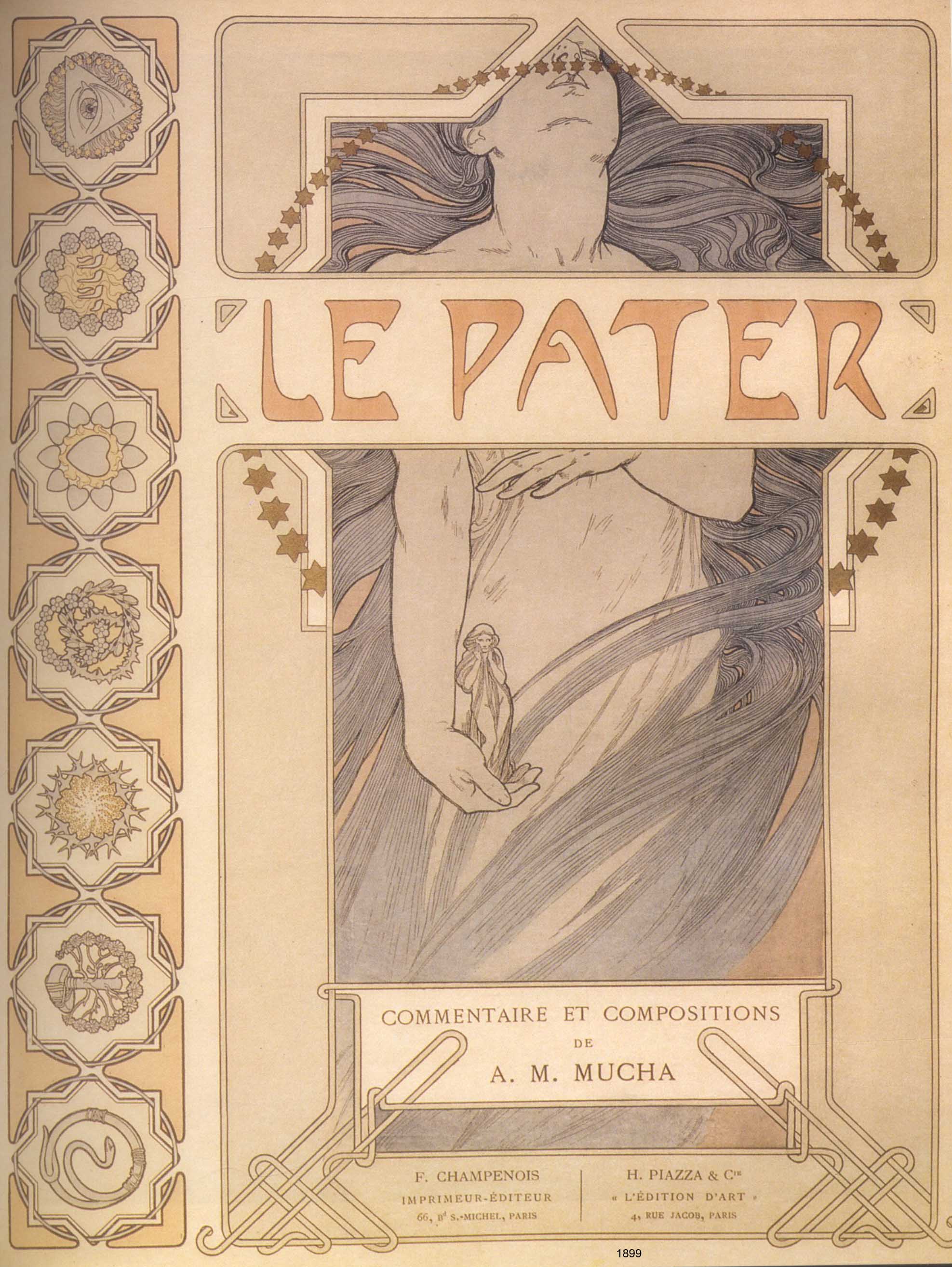

Exhibited pieces of this section presents a brief overview of Alphonse Mucha’s entire work through items and photographs of his artistic and family life. It includes an oddity, a drawing made by Mucha at the age of 8 (Crucifixion, 1868), which demonstrates his inspiration in folk art. Caricatures from his studies in Munich and illustrations for French children’s magazines are of interest. Another group of exhibits, related to the decorative style of the 1890s, suggests the scope and variety of his artistic activities, f.e. Decorative plate, 1897; Designs for a vase or jewellery, ca 1900; including an example from Mucha’s most ambitious book project, the exquisite Le Pater (1899). Related to its impassioned content are examples of expressive pastels and Mucha’s isolated sculptural work - Nude on a Rock, 1899. Mucha’s visits to the United States are documented by a news report and a poster for the Mucha Exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum (1921). His later, patriotic period of work is represented by the sketch for the Mayor’s Hall in the Municipal House in Prague (1910), the famous designs for Czechoslovak banknotes and the design for St Vitus’ Cathedral stained-glass window, Prague (1931). Insignia designed by Mucha for the Czech Freemasonry are also of interest.

Crucifixion (1868)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Nude on a Rock (1899)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Le Pater – title page and two subsequent pages

Mucha considered Le Pater (The Lord’s Prayer) to be one of his best works. It was printed in Paris in an edition of 510 numbered copies (390 in French and 120 in Czech) by Henri Piazza, to whom Mucha dedicated the work.

Mucha wrote of Le Pater: “At that time I saw my path as lying elsewhere, higher. I searched for a means that would spread the light to the remotest corners. I did not have to look long. The Lord’s Prayer. Why not render its text through images?”

In Le Pater, Mucha divided the prayer into seven verses. Each verse is analysed in a set of three decorative pages. On the first page, Mucha presents the verse in Latin and French in a decorative composition of geometrical and symbolic motifs. The second page renders Mucha’s commentary on the content of the verse, imitating medieval illuminated manuscripts in the colour decoration of the initial letter. The third page contains Mucha’s monochrome interpretation of the verse. These visionary illustrations represent man’s struggle on his path from the darkness into light.

Le Pater (1899)

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017

Photos of Mucha's family and friends / Photos of Mucha's studio and his models

© Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017